World champion sprinter Yohan Blake had just raced across a track at a meet in Jamaica when he made his position clear: He would rather miss this summer’s Tokyo Olympics than get a coronavirus vaccine.

“I am not taking it,” he told The Gleaner, a daily newspaper on the island. “I don’t really want to get into it now, but I have my reasons.”

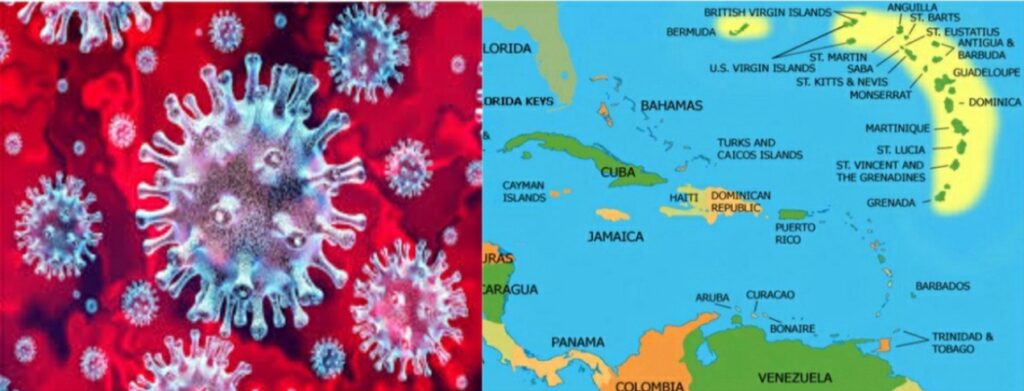

Blake’s reluctance to get a shot to protect himself from the virus that has overwhelmed hospitals in his country underscores a challenge facing health officials across Latin America and the Caribbean as inoculation campaigns get underway: resistance to getting the vaccine.

“His position unfortunately is not that uncommon in many segments of our population,” Jamaica Health Minister Christopher Tufton said of Blake, considered the second fastest man in the world after Usain Bolt. “The difference, of course, is that he is a national talent and therefore carries influence, especially among the younger population.”

As the first vaccine shipments from a United Nations-backed initiative known as COVAX begin arriving in the region, a year after the first infections were confirmed and months after the United States and the United Kingdom began inoculating their citizens, governments are quickly realizing that the race to controlling the deadly pandemic is strewn with distrust, conspiracy theories, and an anti-vaccine campaign growing in strength.