[Reprinted: Jamaica Observer, 9-13-2020]

In recognition of the potential health threats to the region, the Caribbean Community (Caricom) Heads of Government asserted in their Nassau Declaration of 2001 that “The Health of the Region is the Wealth of the Region”, fully cognisant of the critical relationship between the population’s health status and economic growth.

Following a mandate from the Caricom Heads of Government, a task force, the Caribbean Commission on Health and Development (CCHD), was established in 2003 to formulate a framework and a set of strategies to actualise the 2001 Nassau declaration. The task force report recognised chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as the key contributors to overall mortality and morbidity in the Caribbean. According to the report, cardiovascular diseases (high blood pressure, coronary heart diseases, and stroke), diabetes and cancer accounted for 51 per cent of the deaths in the region in the latter part of the 1990s.

The rise in cardiovascular diseases is not restricted to the elderly. Jamaica is also experiencing an alarming rise in cardiovascular-related diseases among young people. In early 2018, a report found that in 2017, 30,000 children in Jamaica between the ages of 10 and 19 had been diagnosed with hypertension. Similar trends are seen with diabetes, another promoter of cardiovascular diseases. There is data to suggest that more adolescents in Jamaica become obese at an early age and therefore at an increased risk for developing type II diabetes. As many as 19 per cent of adolescents in Jamaica are considered obese. An estimated 20 per cent of diabetics in this population are afflicted with type II diabetes.

The 2006 CCHD report showed that the cost of hypertension and diabetes in Jamaica for the year 2002 alone was estimated to be about US$ 58.5 million, without including the economic value of the premature death that these diseases cause.

The economic cost associated with cardiovascular diseases has continued to escalate. While speaking at the launch of the 2017 Reggae Marathon, Half Marathon and 10K at the Alhambra Inn in St Andrew on October 24, 2017, Minister of Health Dr Christopher Tufton was credited as saying that it will cost Jamaica approximately $77 billion over the next 15 years to treat people suffering from cardiovascular-related diseases and diabetes. Without critical attention and creative re-imagination, it is difficult to see how Jamaica can support or sustain such costs while attending to other critical needs of the society.

The CCHD report emphasised the critical need for effective and appropriate treatment and management of these diseases when they occur and to establish surveillance systems to effectively monitor lifestyle or behavioural risks to inform policymaking as well as public education and prevention campaigns.

On September 15, 2007, prime ministers of Caribbean countries met in Port of Spain, Trinidad, in the First Caribbean Summit on Chronic Diseases and signed a declaration for the prevention of chronic diseases in the Caribbean countries. This declaration, in theory, represented a major regional assault against chronic non-communicable diseases and is intended to galvanise and mobilise the region against a cluster of health risks that include obesity, high blood pressure and diabetes. Unfortunately, nearly 15 years later, we have not taken the necessary bold steps to restructure our health care delivery systems to meet the needs of today. Non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, and certain cancers now account for 70 per cent of total deaths in Jamaica.

We need health equity and uniform standards

To properly position Jamaica to take advantage of the various opportunities that exist to improve access and quality of care for all Jamaicans, it is imperative that we evolve an approach that places a premium on health equity, utilising the inherent capacity in both public and private health care sectors to ensure equal access to optimal services for all Jamaicans within a set of uniform standards and regulations for both public and private facilities as the intended outcome of a viable health care system in the island.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of physical, psychological and spiritual well-being, and not merely an absence of diseases. Health, as a state and outcome, is impacted by the complex interaction of many variables: individual, social, and economic. The human capital perspective on health recognises an initial endowment of health, which can be maintained, and enhanced by health production processes, including but not limited to health care”.

A multi-pronged initiative is needed to explore the future of health care services and delivery in Jamaica taking advantage of advances in science and technological breakthroughs in battling acute and chronic illnesses. The engagement of a diverse cross-section of health care stakeholders including providers, payors and consumers of health care services is essential to developing effective and non-discriminatory health care delivery system, operating under the same regulatory and compliance standards and serving all Jamaicans equally without the normalisation of poor standards and outcomes for the poor and underprivileged while preserving optimal care only for the rich and well-placed.

It is important to identify common ground amongst stakeholders that could serve as the basis of future collective action to advance the process of health care reform. This should recognise the transformative value and cost effectiveness of public-private sector partnerships that would reduce wastage, optimise and promote the cost effective use of human capital and technology in health care delivery to broaden access to high quality care to all Jamaicans.

The vision for effective health care delivery in Jamaica must start with a paradigm shift that recognises the immense technological advances and monumental research advances in health care that have largely been restricted in availability mainly because bureaucratic bottlenecks and our failure to creatively leverage our collective resources within the entire health care ecosystem to make such services more universally accessible to the population at large. Unless we use smart and creative approaches, the technology and research that are essential for maintaining a good quality of life will not be within the reach of ordinary Jamaicans because of cost implications. For Jamaica to benefit from these advances in medicine, we must increase appropriate investments in the health care value chain and modernise our health care infrastructure while promoting our primary health initiatives.

Effective modern diagnostic and treatment strategies are critical elements in the maintenance of good health in all societies, especially in the light of overwhelming evidence supporting the link between good health, wealth, and economic growth. There is overwhelming amount of data supporting the notion that the healthier nations are also the more prosperous nations, supporting the argument that nations which make sustainable health care investments are more likely to enjoy sustainable economic growth. The rationale is quite simple; a healthier population equals a more productive work force. A more productive workforce leads to a more sustained economic growth, more employment, and more revenue base for the Government. To achieve sustainable gains in health indices, Jamaica must embrace collaborative care and technological progress to enhance our health systems. The advances and opportunities are enormous and can be ignored only at significant peril.

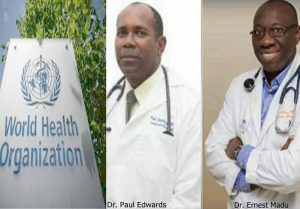

About the authors: Dr Ernest Madu, MD, FACC, and Dr Paul Edwards, MD, FACC are Consultant Cardiologists at Heart Institute of the Caribbean (HIC) and HIC Heart Hospital.