A side effect of the COVID-19 vaccine is raising concerns about the accuracy of mammography results and questions about whether recently vaccinated patients should delay or move forward with scheduled screenings.

A new study out of Massachusetts General Hospital reports that the shot can cause lymph nodes to swell similarly to how they would when breast cancer spreads to them. Some physicians are worried such an adverse event could create unnecessary worry and lead to false positive diagnoses for breast cancer.

Some have recommended that patients who have received the vaccine delay mammograms, biopsies and additional imaging, while others say screenings should continue on as scheduled.

“Some have recommended waiting four to six weeks after your final vaccine dose before having a mammogram. That way, any lymph node swelling caused by the vaccine has time to go away. Others, including Mayo Clinic, recommend that mammograms continue as scheduled. But be sure to tell your doctor about your vaccination, the date it occurred and which arm was affected,” Mayo Clinic posted on its website.

Swollen lymph nodes under the arm in which the vaccine is administered indicates that the body’s immune system is responding and building up antibodies against the virus that causes COVID-19. Similarly, the spread of breast cancer can cause lymph nodes in the armpit to swell.

Out of the 70 million vaccinated already in the U.S., over 85% reported local reactions at the injection site and 75% reported systemic reactions. Axillary swelling or tenderness was the most common unsolicited adverse event reported, with 10.2% of patients experiencing it after the first Moderna vaccine and 14.2% of patients after the second. Known as palpable unilateral lymphadenopathy, the condition has also increased among those who received the Pfizer vaccine, according to the MGH study.

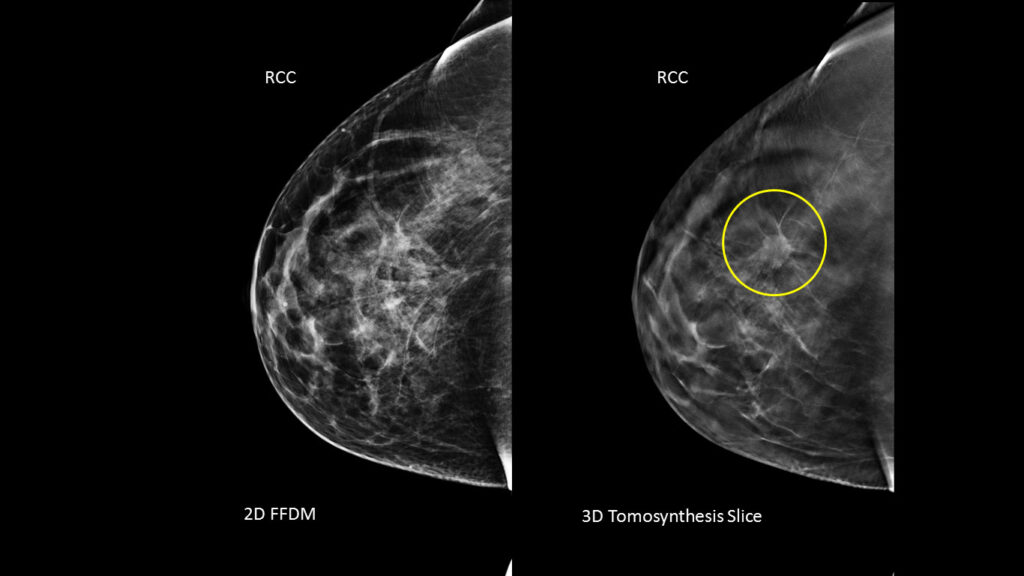

The Society of Breast Imaging recommends that women receive mammograms before they receive the vaccine and that those who already have wait four to six weeks before scheduling one and four to 12 weeks for follow-up imaging after receiving the final dose. “Breast radiologists will increasingly encounter axillary adenopathy as more patients become vaccinated, but the near to long term appearance of mammographic adenopathy following vaccination is currently unknown,” it said in a statement, adding that “if axillary adenopathy persists after short term follow up, then consider lymph node sampling to exclude breast and non-breast malignancy.”

The study’s authors, however, advise against rescheduling imaging or vaccinations due to it potentially deterring racial and ethnic minorities from seeking medical support in the future. Such populations are more likely to suffer from both COVID-19 and cancer, write the authors. “In the specific setting of dramatically increased barriers to routine health care and strained healthcare resources due to the pandemic, we continue to focus our efforts to bring patients in for recommended imaging and to use a pragmatic approach for our radiologists and healthcare team to manage UAL in the setting of recent vaccination.”

They add that low-test probability shows that ipsilateral UAL can be managed clinically without advanced imaging of malignant lymphadenopathy, and advise clear communication between patients and providers to reduce confusion. This can be done through recording vaccination status, advanced planning, and sending out letters about side effects of the vaccines to patients.